Expiration of the Licensing Act

In 1557, the Company of Stationers - a guild composed of 97 freemen from London and its suburbs - was granted a monopoly on printing in the realm, except for certain sites that had received special royal permission, such as Oxford and Cambridge universities. This limitation was a remedy inspired by Queen Mary and her husband, Philip, king of Spain, against “seditious and heretical books.” Eventually, the number of printer-publishers declined in the company as bookseller-publishers increased, and the government adopted a spirit of deregulation. Because these changes had eroded the company’s power, the Licensing Act protecting the Stationers’ monopoly was allowed to lapse in 1695. Thus, printers were set free thereafter to practice their trade in such provincial locales as Birmingham, Chester, and Salisbury.

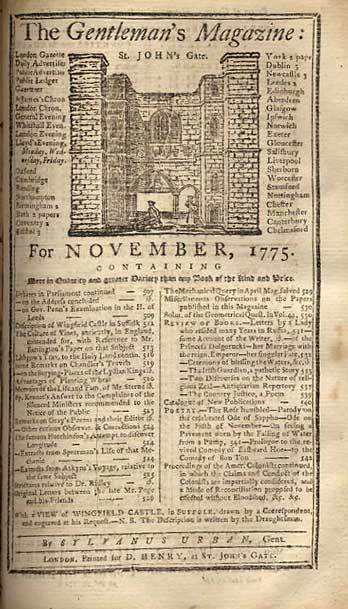

Although some 18th century provincial printers did become involved in producing books, these were the exception rather than the rule. Most books continued to be printed in London because of the capital city’s greater resources, and the London tradesmen’s somewhat elitist attitude. But the lapse of the Licensing Act did have an important impact in stimulating the growth of journals and newspapers, which were less expensive to produce than books and thus more attractive to provincial printers. Fueled by the turbulent politics of the century, as well as heated business and personal rivalries, journals such as The Spectator (printed outside of London) and The Tatler provided a forum for satire and commentary about the news of the day. Newspapers, bolstered by improved transportation during the 1700s, were distributed throughout England. In 1702, there was only one regular newspaper published outside of London; by 1750, at least 40 provincial newspapers were in circulation.