Education and Literacy

Education was the tool for bringing literacy to the growing lower and middle classes in 18th century England. The spirit of this age of Enlightenment fostered a general desire for intellectual improvement and once larger segments of the population had learned how to read, they eagerly snapped up books, almanacs, and other reading materials on subjects ranging from agriculture to theology.

English public schools for boys, such as Eton, were in disarray during the 1700s, plagued by corruption and committed to a classical curriculum that many regarded as impractical. Moreover, their resources were inadequate to serve a growing population. However, Anglican charity schools, begun by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (founded in 1699), offered an alternative that served both boys and girls. The charity-school movement faded around mid-century, but by the end of the century, Anglican Sunday schools (the first of which was founded in 1780 by printer Robert Raikes) had become popular—Sunday being the one day on which children were “free” from their jobs in factories. Workhouses also developed schools for their young laborers, patterned on a model suggested by philosopher John Locke in 1697. The commercial classes favored sending their children to private schools, where the curriculum was more practical than at the public schools.

The numerous dissenting religious groups, such as the Unitarians, Methodists, and Quakers, also founded schools in the 1700s to influence their young members’ minds and morals.

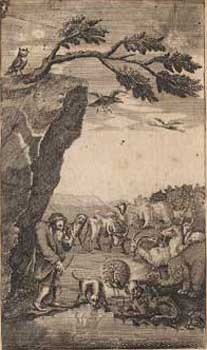

All of these schools, of course, required textbooks, a demand that booksellers were eager to fulfill. Among the commonly used texts in the charity schools was Aesop’s fables—part of an increasing amount of reading material aimed at youth.

Such crucial reference works as dictionaries and encyclopedias also made their English debuts during the 18th century.