A Common Thread Between Book Arts and Environmentalism

Johanna Drucker considers a strain of artists’ books as “democratic multiple.” Artists’ books can address any topic, can be crafted inexpensively or use the finest quality materials, and can reach a broad audience through mass distribution, in libraries and through exhibitions.[i] Drucker asserts that book arts developed into an expressive artform in the middle of the twentieth century, largely for the sake of social change, along with the “emergence of various avant-garde movements.”[ii] She elaborates, “Following the mid-century, artists began to make books a primary or major aspect of their activity, without linking the content or form of the book to an already established agenda.”[iii]

The development of artists’ books coincides with the formalization of the environmental movement and in some ways it seems the two are linked. Betty Bright points out that The Whole Earth Catalog, a seminal journal centered on environmentalism, included references to bookmakingand printing in its first edition in 1968 and also in a subsequent edition.[iv] Bright immediately acknowledges in her book, No Longer Innocent: Book Art in America 1960-1980, that scholars “still lack a generally accepted and workable definition of artists’ books.”[v] This is also the case for art that can be associated with environmentalism.[vi] She additionally notes, “Book workers as a rule show affinities with the avant-garde movements of their time.”[vii] As the eco-art movement is relatively new and is steeped in activism, it is no surprise that book arts have embraced this activist driven genre. These two seemingly disparate practices evolved concurrently to promote issues to various audiences, from grassroots movements to collectors of fine arts.[viii] Unfortunately, book arts and the environment also share in common the concern of endangerment. While some of the artists’ books in Special Collections address issues of endangered species, monocultures and altered landscapes, the art of book making is also threatened in some places.[ix]

In 1992 Bright curated Completing the Circle: Artists’ Books on the Environment at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. Bright reports that the show was criticized by book enthusiast Abe Lerner who took issue with sculptural book works. She empathizes, “These books are not pretty, and they do not follow the rules of typography or binding or, for that matter, reading itself.”[x] Twenty-four years later, Bright’s curatorial exploration of artists’ books on the environment deserves a second approach, not only because there is much work to be done in service to the environment, but also because many artists’ books surrounding the topic have been made since 1992. If nothing else, the books included here are actually quite “pretty.”

With the progression of book making in the twentieth century, Bright comments, “Books were no longer viewed as repositories of finite meaning, but rather as permeable membranes whose information could yield multiple interpretations, even as they effortlessly crossed geographical (and political) boundaries.”[xi] She condoles, “The restriction of exhibition in display cases force readers and critics to judge and articulate a book’s success based on a single page opening. Reading a book involves the tactile, even emotional experience of paging through it.”[xii] For this and other practical reasons, the artists’ books in ECO Ephemeral are available for viewing and handling in Special Collections throughout the duration of the exhibition.

[i] Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists' Books, (New York: Granary Books, 1995), 69.

[ii] Ibid., 1.

[iii] Ibid., 71.

[iv] Betty Bright, No Longer Innocent: Book Art in America 1960-1980, (New York: Granary Books, 2005), 97.

[v] Ibid., xiii.

[vi] The term “eco-art” is particularly contested. Definitions contradicting Weintraub’s usage have been suggested by Christoph Brunner, Roberto Nigro and Gerald Raunig who reflect on Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, translation by Ian Pinder and Paul Sutton, (London: Continuum, 2008) 35-36. Christoph Brunner, Roberto Nigro and Gerald Raunig, “Post-Media Activism, Social Ecology and Eco-Art.” Third Text, January, Vol. 27, Issue 1 (2013): 10, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2013.752200.

[vii] Bright, No Longer Innocent, xiii.

[viii] Ibid., 6-7.

[ix] As an example, in 2015 my alma mater, Mills College, proposed plans to close its respected Book Arts program. Sarah Burke, “An Identity Crisis at Mills College,” Eastbay Express, November 4, 2015, accessed May 29, 2016, http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/an-identity-crisis-at-mills-college/Content?oid=4563237. Further, artists’ books are underrepresented in museum exhibitions.

[x] Bright, No Longer Innocent, 1-2.

[xi] Ibid., 193.

[xii] Ibid., 7.

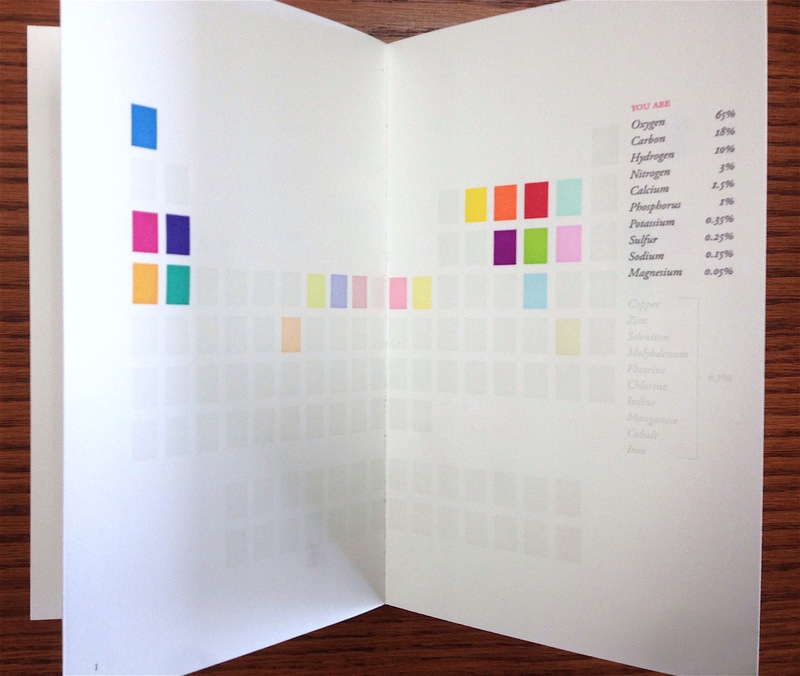

Figure 6

Sarah Bryant

Biography 2010

Aurora, NY: Big Jump Press

8¾ x 5½ x ¾ in.

Edition 23 of 75

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

Discussing the books by creator, in alphabetical order, serendipitously happens to arrange the books in a sort of narrative. It is especially fitting to start off by focusing on Sarah Bryant’s Biography (2010, fig. 6). Bryant’s book is letterpress printed from polymer plates on Zerkall Book paper, is drum-leaf bound in hard cover and is enclosed in a clamshell box. Bryant was influenced by her colleague Jessica Peterson to include exactly twenty colors, a situation that Bryant adoringly begrudges.[i] There is a strong emphasis on the graphic design which Bryant accomplished using InDesign for the layout. She then transferred the digital files to polymer plates, which are a photosensitive plastic material that hardens when exposed to light. Such plates are typically used for relief printing but in this case they also offered Bryant a practical way to transfer the digital files to a traditional printing process. Made on a Vandercook press, Biography combines relief printing and pressure printing.[ii]

Bryant worked on Biography while she was a fellow at Wells College. The project began with visual studies of the periodic table as an offshoot of topics she addresses in her earlier books. She wanted to make a new work that was clever but was also a somewhat “arbitrary crazy book.”[iii] The title refers tangentially to Bryant herself, but more broadly to the makeup of human physiology and ecology. Although the book is not reliable for significant scientific data, she made a concerted effort to convey accurate information by consulting Professor Christopher Bailey, Chair of Biological and Chemical Sciences at Wells College. As she explored the periodic table in printmaking she determined that she needed to focus on a specific topic with respect to chemistry “because the periodic table is so much – it is everything.”[iv] As the human body had been a subject of interest in her previous projects, she built on this idea and considered the elements in the human body and how humans relate to their environments. One of the fascinating correlations that she presents in her book is that pesticides and fertilizers contain some of the same elements. Contradicting logic, we use chemicals that kill in order to grow food. She outlines similar relationships between medicine and weapons.[v] The book includes nine diagrams designed by Bryant:

1. You are what you are made of

2. You are part of something larger than yourself

3. You are what you stand on [refers to the crust of the earth]

4. You are what you make [refers to weapons, medicines, tools, etc.]

5. You are what you make (part 2)

6. You are what is similar to you [is a list of animals]

7. You are where you came from [notes the proportion of elements in sea water]

8. You are

9. You are

[i] Sarah Bryant, “The Evolution of an Artist’s Book by Sarah Bryant,” The Susan Garretson Swartzburg Lecture Spring 2011 lecture at Wells College, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2016. http://video.syr.edu/Video.aspx?vid=TlzP3UMBD0O45MptqQ5DuA.

[ii] A deluxe version in an edition of ten copies includes all of the prints that were made simultaneously with the book.

[iii] Bryant, “The Evolution of an Artist’s Book by Sarah Bryant.”

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

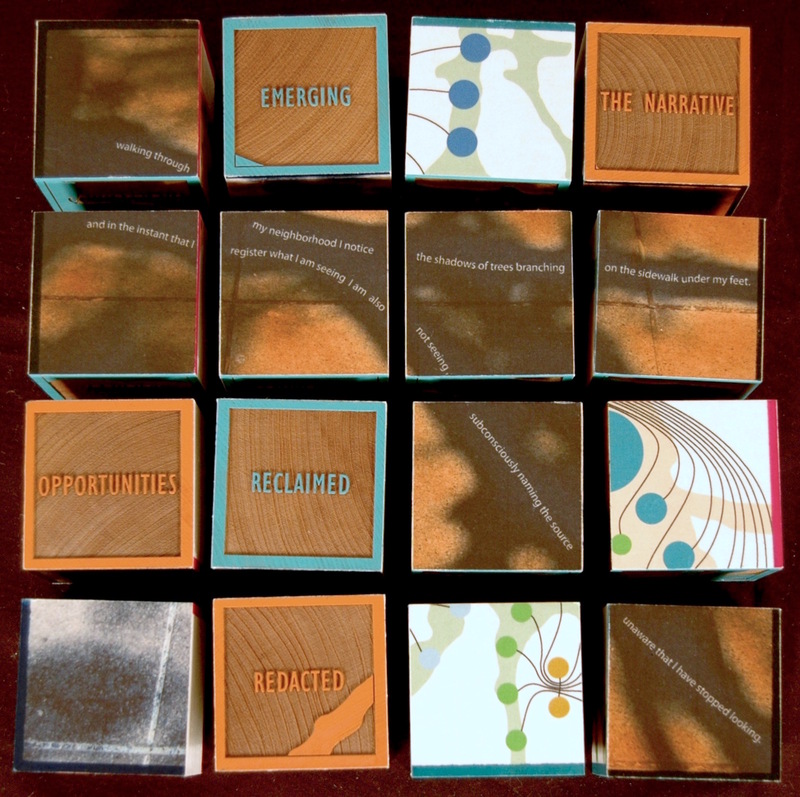

Figure 7

Julie Chen

Family Tree 2013

Berkeley, CA: Flying Fish Press

2¾ x 9 x 9¼ in.

Edition 36 of 50

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

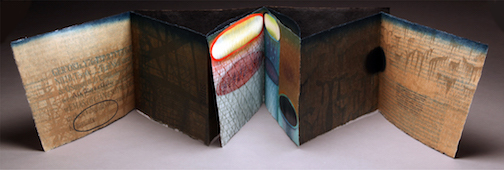

Julie Chen’s Family Tree (2013, fig. 7) is a hybrid livre de luxe (sculptural bookwork) contained in a cloth covered solander box.[i] The work is comprised of a block puzzle. Each block includes four digitally printed sides and two laser-engraved sides that form six predetermined arrangements and allow for infinite groupings. Bright equates the structure of some artists’ books to children’s books: “The presence of nostalgia suggests an unrecoverable past, a sense of loss that might arise with a reader’s encounter of such a format from childhood.”[ii] Chen’s work demonstrates this situation perfectly in tandem with concern for the environment. The blocks show the following texts when the six puzzles are matched and turned congruently:

walking through my neighborhood I notice the shadows of trees branching on the sidewalk under my feet. and in the instant that I register what I am seeing I am also not seeing. subconsciously naming the source unaware that I have stopped looking.

CONNECTIONS EMERGING AFTER DORMANCY

IDENTITY REINVENTED THROUGH INTERPRETATION

EVENTS RECLAIMED RECTIFYING ASSUMPTIONS

FAMILY LINKED BEYOND BLOODthinking about my personal history I consider the connections linking me within a web of abstractions. over my lifetime I have accumulated many selves, inadvertently creating an unidentifiable person within a framework of familiarity.

PATTERNS HIDDEN BENEATH THE NARRATIVE

GENERATIONS FORGOTTEN DUE TO NEGLECT

OPPORTUNITIES LOST MASKING THE TRUTH

HISTORY REDACTED BY INDIFFERENCECONNECTEDNESS EXPLAINED THROUGH CONTACT

CONNECTEDNESS EXPLAINED THROUGH TIME

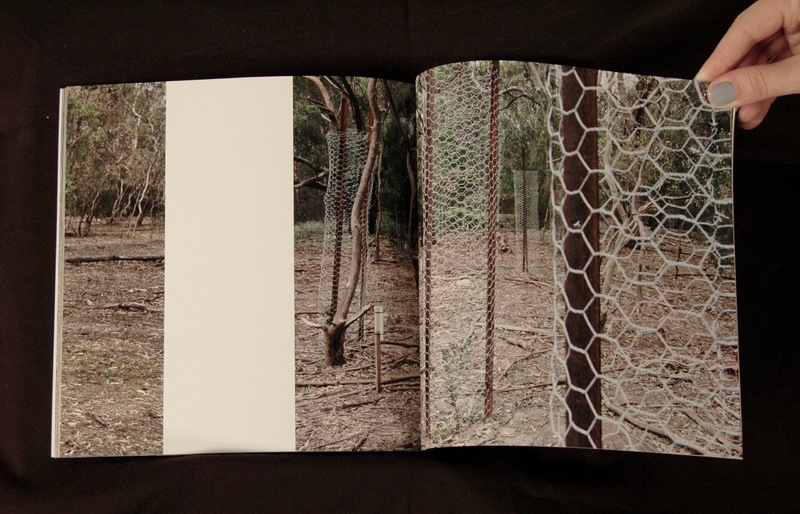

Figure 8

Eddee Daniel

Wildlife Sanctuary 2016

MagCloud

8 x 8 x ¼ in.

Unlimited copies

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

Eddee Daniel, based in Milwaukee, recently published Wildlife Sanctuary (2016, fig. 8) using an online, print on demand service. This newer form of book art cannot be dismissed for its commercial production because it has roots that spread back to early production of books that were used to circulate messages widely at a nominal cost, including chapbooks, Fluxus publications and zines. Even Edward Ruscha’s acclaimed books employ this method. Despite the careful design that Ruscha dedicated to his book layouts, Drucker notes that the use of standard printing techniques is a distinguishing feature of his books, as in Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963).[i]

Wildlife Sanctuary presents ironic imagery of a preserve at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia. The seventy-four acre sanctuary is a space for education in restoration and management of native flora and fauna. Daniel’s photography displays the odd intersection between urban life and revitalization of natural habitats. Although it is much greater in scale, it shares distinct similarities with Downer Woods at the UWM Kenwood Campus where a fence effectively locks in the natural growth in order to protect it from human activity. The images coincide with Daniel’s attraction “to contradictory realities in a world increasingly compromised or redeemed by our own actions.”[ii]

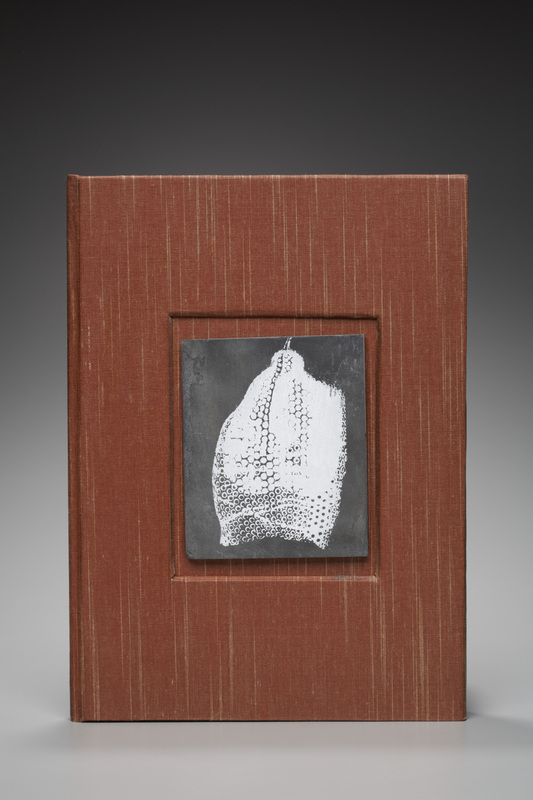

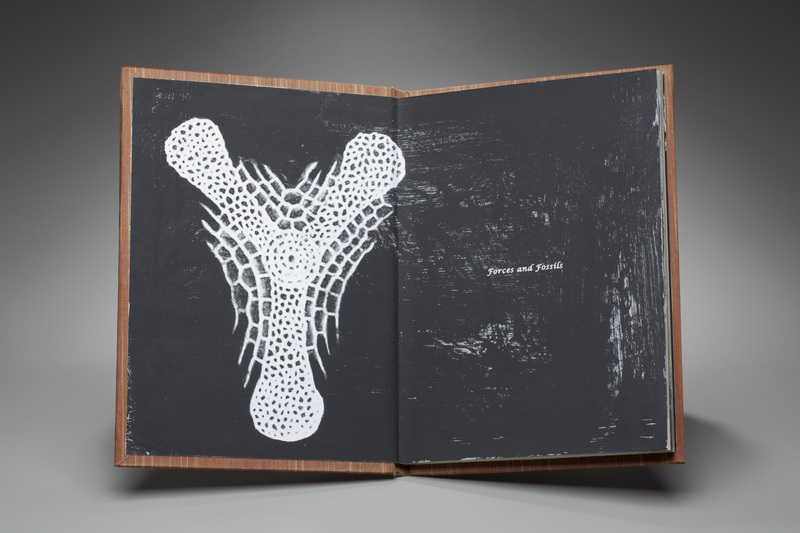

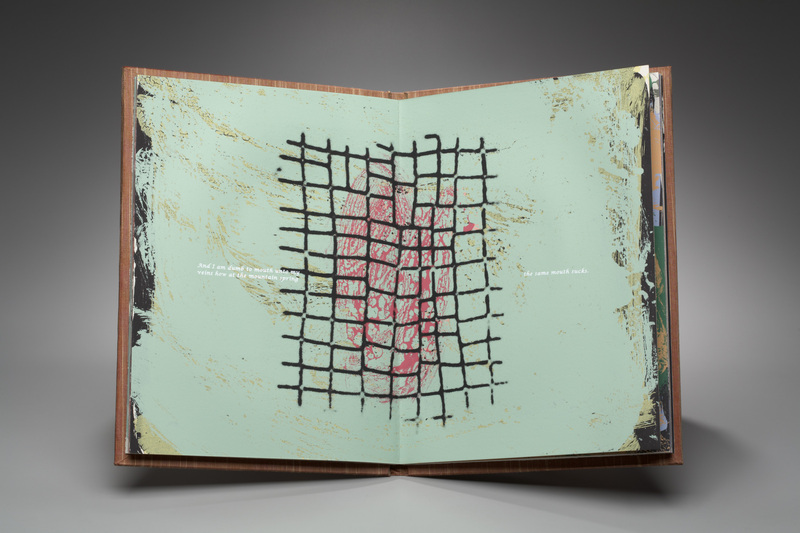

Figure 9

Fred Hagstrom

Forces and Fossils 2011

Edited by Dylan Thomas, Ernst Haeckel and Strong Silent Type Press. St. Paul, MN: Strong Silent Type Press

15⅝ x 11⅛ x 1 in.

Edition 4 of 20

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

Fred Hagstrom

Forces and Fossils 2011

Edited by Dylan Thomas, Ernst Haeckel and Strong Silent Type Press. St. Paul, MN: Strong Silent Type Press

15⅝ x 11⅛ x 1 in.

Edition 4 of 20

Fred Hagstrom

Forces and Fossils 2011

Edited by Dylan Thomas, Ernst Haeckel and Strong Silent Type Press. St. Paul, MN: Strong Silent Type Press

15⅝ x 11⅛ x 1 in.

Edition 4 of 20

Fred Hagstrom is well represented in Special Collections, thus it was difficult to choose just one work of his to feature in this exhibition. Paradise Lost, which addresses the atrocities of nuclear testing on Bikini Atoll in the 1940s and 1950s, seemed like an obvious choice, particularly in conjunction with Ferrella’s remarks about nuclear testing west of America’s breadbasket. However, Paradise Lost can be explored in the digital exhibit Another Place.[i] An alternate work by Hagstrom that is equally appropriate in the context of ECO Ephemeral is Forces and Fossils (2011, fig. 9). This book is screen-printed using illustrations from German naturalist Ernst Haekel’s book Radiolaria (1862) and includes the complete text of Dylan Thomas’s poem The Force that through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower (1939). The large and heavy book is drum leaf bound with a screen-printed piece of slate inset on the front of the hardcover.

The radiolarian images represent fossils of minute protozoa found throughout the ocean floor. Thomas’s poem can be interpreted in many ways, but it can be inferred that it is about human naiveté against Mother Nature. This poem, included below, presents uncanny parallels to the themes explored in Bryant’s book, Biography.

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees is my destroyer. And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose my youth is bent by the same wintry fever. The force that drives the water through the rocks drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams turns mine to wax. And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins how at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks. The hand that whirls the water in the pool stirs the quicksand; that ropes the blowing wind hauls my shroud sail. And I am dumb to tell the hanging man how of my clay is made the hangman’s lime. The lips of time leech to the fountain head; love drips and gathers, but the fallen blood shall calm her sores. And I am dumb to tell a weather’s wind how time has ticked a heaven round the stars. And I am dumb to tell the lover’s tomb how at my sheet goes the same crooked worm.

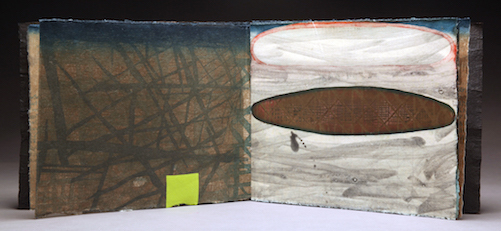

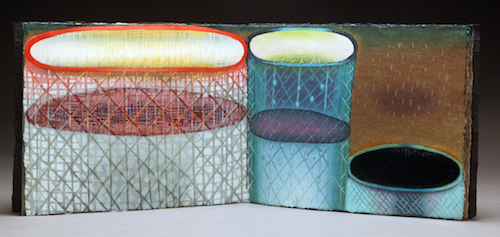

Figure 10

Karen Kunc

Air, Water, Oil 2010

Avoca, NE: Blue Heron Press

8 x ¼ x 10½ in.

Edition 5 of 10

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

Karen Kunc

Air, Water, Oil 2010

Avoca, NE: Blue Heron Press

8 x ¼ x 10½ in.

Edition 5 of 10

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

Karen Kunc

Air, Water, Oil 2010

Avoca, NE: Blue Heron Press

8 x ¼ x 10½ in.

Edition 5 of 10

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

Karen Kunc

Air, Water, Oil 2010

Avoca, NE: Blue Heron Press

8 x ¼ x 10½ in.

Edition 5 of 10

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

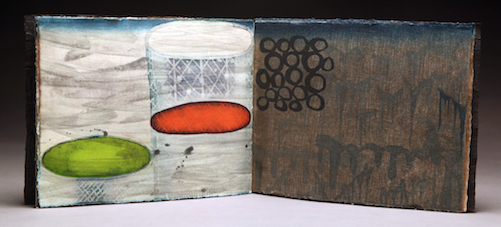

Karen Kunc’s Air, Water, Oil (2010, fig. 10) is a pamphlet stitched book with a black handmade-paper cover that has deckled edges. Although it is a simply constructed book it has some carefully crafted surprises. There are two leaves that are tri-folded and the final spread is forty-one inches wide. The pages also have an unusual waxy appearance. Kunc explains, “The prints were treated with acrylic washes, that pooled and stiffened the papers to make them carry the sense of liquid ‘stuff.’”[i] Ovals are repeated throughout the book, reminiscent of ships or oil tankers, and a grey haze covers the pages, simulating smoggy air. Black drips and smears recall imagery of random oil spills. Kunc searches her memory. “I can't remember exactly what was happening at the time I made this work, but I often address natural and man-made disasters, the daily science stories and discoveries, the ecological and economically entwined issues that color our everyday decisions. I am not didactic in approach, but my visual vocabulary implies and suggests.”[ii] In her formal statement about the book she acknowledges the duality that often comes between art and environmentalism: “The content mirrors the human dilemma of the use of natural resources, as the color reduction woodcut process destroys once living matter – in the creation of something meaningful.”[iii]

Figure 11

Denise Levertov and Claire Van Vliet

Batterers 1996

Edited by Claire Van Vliet, Kathryn Vigesaa Lipke and Janus Press. West Burke, VT: Janus Press

12⅛ x 15¼ x 2⅞ in.

Edition of 100

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

early version of one of Lipke Vigesaa’s “Earthskins”

pressed clay-paper

1996

The earliest work included in the exhibition is Denise Levertov’s Batterers (1996, fig. 11), which was truly a collaborative effort with Claire Van Vliet, Katie MacGregor, Bernie Vinzani, Kathryn Lipke Vigesaa, Jack Sumberg, Judi Conant and Mary Richardson. Batterers is visually commanding and conceptually stunning. A large clamshell slipcase is covered repeatedly with the title in bold sans serif type of varying sizes, as if to pound the title into the viewer’s psyche. Inside the slipcase is a wooden shadowbox with overlapping accordion folds pigmented in scarlet red. Within three sections, a poem by Levertov is revealed:

A MAN SITS BY THE BED OF A WOMAN HE HAS BEATEN, DRESSES HER WOUNDS, GINGERLY DABS AT BRUISES, HER BLOOD POOLS ABOUT HER, DARKENS.

ASTONISHED, HE FINDS HE’S BEGUN TO CHERISH HER. HE IS TERRIFIED. WHY HAD HE NEVER SEEN, BEFORE, WHAT SHE WAS? WHAT IF SHE STOPS BREATHING?

EARTH, CAN WE NOT LOVE YOU UNLESS WE BELIEVE THE END IS NEAR? BELIEVE IN YOUR LIFE UNLESS WE THINK YOU ARE DYING?

Claire Van Vliet wrote a letter that accompanies the book in which she mentions that Levertov wrote the poem with the second and third verses being interchangeable. This layout allows the reader to choose equitably. The obverse of the shadowbox could easily be overlooked, as is so much of the scarring of the earth, however it is intended to double as the cover and as a framed work. It is an early version of one of Lipke Vigesaa’s “Earthskins” made of pressed clay-paper, which forms a muddy, rock-like landscape with deep wounds.

Batterers was created when ecofeminism was peaking in the scholarly realm during the mid-1990s. In 1997 Karen Warren wrote in the introduction of her book Ecofeminism: Women, Culture, Nature that “ecological feminism is the position that there are important connections between how one treats women, people of color, and the underclass on one hand and how one treats the nonhuman natural environment on the other.”[i] Levertov approached this issue assertively in 1996. A full twenty years later, the term “ecofeminism” is wildly radicalized by political conservatism and it is not clear that any gains have been made in mitigating human rights abuses, animal abuse or abuses against the environment.

[i] Karen Warren and Nisvan Erkal, Ecofeminism: Women, Culture, Nature, (Indiana University Press, 1997), 3.

Figure 12

RegulaRusselle

On Hospitality 2014

St. Paul, MN: Cedar Fence Press

7¼ x 7¼ x 3¾ in.

Edition of 6

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

As ecofeminism hasn’t penetrated mainstream thinking, environmentalists have gradually adopted the approach of “kill ‘em with kindness.” Regula Russelle’s On Hospitality (2014, fig. 12) demonstrates this point perfectly. Within a sturdy square box Russelle includes four objects in individual origami boxes. A small accordion-fold book spreads out over thirty-three inches and three handmade paper sculptures in the form of vessels nestle like eggs. The title and delicate contents of the box evoke a sense of responsibility upon the viewer. To hold one of the paper vessels is like being given an egg to carry like a baby. Each vessel contains a word or a series of words composed by Russelle, and a quote by Lao Tzu is presented as a prelude to the text in the book:

Doors and windows are cut from walls to form a house;

but it is on the empty space within, that its use depends.Lao Tzu

gate, hail approach with open arms bid welcome receive & usher in, cultivate, ear hear, heart hearth, compose & form, assemble, mend, consolation, dwelling, abide, ORCHARDS, CHOIR, LIBRARIES, tending over time, ask: what does it mean to host a pilgrim soul?[i]

Figure 13

Jody Williams

Still Sense 2008

Minneapolis, MN: Flying Paper Press

2¾ x 2¾ x 2¾ in.

Edition 41 of 75

UW-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections

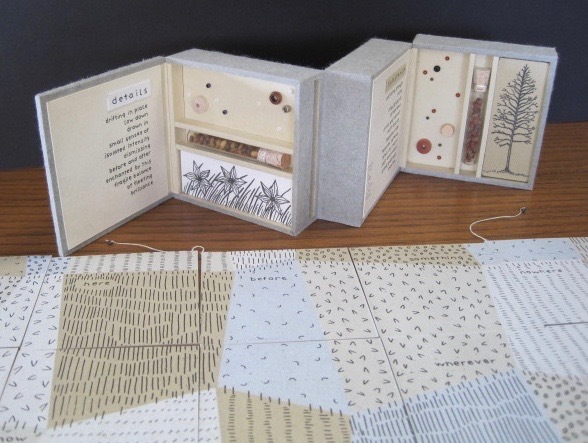

Jody Williams’ Still Sense (2008, fig. 13) is reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase, 1936-41). With respect to Boîte-en-valise Bright notes, “A strength of its boxed format is that it allows access to its contents and also embodies the circularity inherent in artistic process, rather than submitting to a book’s linear structure.”[i] Williams takes this non-hierarchal structure a step further by enclosing three sets of six puzzle pieces within narrow cavities along the edges of the case. The book is constructed from bookbinder's board covered in Momi paper, and Sakamoto paper lines the interior. Inside the color coded shell-like pages there are beads and three corked glass vials that are filled with specimens from the Minnesota terrain, representing flowers, trees and grasses.

The puzzle-like cards are illustrated using intaglio and are color coded on one side to correspond with their home in the case. Williams thoughtfully intertwines multiple concepts in threes: “three boxes, three themes (Details, Essence, Substance), three elements (text, image, specimen), three botanical types, three sets of loose cards, three colors, three dimensions.”[ii] The enclosed text follows:

Details (white)

drifting in place

low down

drawn in

small senses of

isolated intensity

dismissing

before and after

enchanted by this

fragile balance

of fleeting

brilliance

Essence (blue)

reaching out

suspended beyond

a complex plain

becoming something else

almost the sky

waves of questions

consuming

illusions of profundity

only this

still sense

prevails

Substance (brown)

gathering strength

rising

singular points

of reference

divide and connect

earth and sky

imposing order

repeating patterns

retain and record

past and present

grand presences

enduring

All of the puzzle pieces fit together to read:

here, before, something, nowhere, never

now, that, wherever, always, nothing

soon, the other, somewhere, after, everything, everywhere

When the pieces are flipped congruently the three sets of cards show the following text:

(white)

intimate, distinct

ephemeral, elegance

precision, radiance

(brown)survival, enduring

solid, spreading

structure, intent

(blue)subtle, transcending

dimension, complete

whisper, mystery