Gender

While mass media often portrays nurses as flirtatious, it also portrayed careers as being incompatable with domesticity. Conservative domestic ideologies of the mid-twentieth century often discouraged women from working after marriage, yet labor statistics reflected that in fact greater numbers of women continued to work after marriage. One wonders then if once one of these flirtatious nurses has landed herself a husband, can she continue her work?

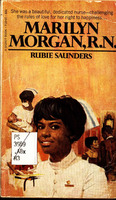

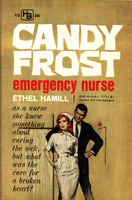

Open up a lightbox gallery of more titles, images, and quotes by clicking each image!

Can a Nurse Be a Wife?

The cover captions of romance novels often insinuate that their nurse-protagonist must choose between nursing and marriage. Indeed, most nursing schools forbade student nurses from marrying while in training.

During World War II, the strict ban on marriage was unofficially lifted; student nurses could gain permission to marry by petitioning both the dean of the school and the director of nursing. Married students were still required to live in the dormitories so as not to disrupt their education or service to the hospital. Curiously, a married student nurse still had to request permission in order to stay off-campus with their husband while he was on leave from the service.

Through much of the 20th century, married women were encouraged to leave their jobs when they married. While many romance heroines were happy to do so, nurse romance protagonists push off marriage in order to enjoy their career—until a man comes along who is happy to have a working wife. In this way, nurse romance authors engineered a story that illustrated what a relationship might look like that didn't adhere to the traditional, domestic ideology.

Stirrings Against Conformity

Authors nodded to the social, cultural, and political fears that permeated the 1950s and 60s. Protagonists challenge the expectations that they should desire marriage and motherhood while secondary characters comment on such matters like the declining moral values of younger generations, fears of rising communism, and atomic threats.

"the problem that has no name"

In 1963, Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique was published and many people credit her for igniting second-wave feminism. But romance scholars had been writing characters for many years whose words and actions anticipated Friedan's arguments. Female characters in nurse romance novels resented being defined by marriage and motherhood alone. The protagonists frequently declare that they are too young to get married or want to experience more of life before settling down, revealing that marriage was at times understood as a barrier to self-fulfillment.

Career Girls, Single Girls, Sex, Divorce

In 1962, Helen Gurley Brown shocked (and delighted) readers with her newly published how-to guide for single, adult, working women. Sex and the Single Girl advocated for young women to focus on a career, live in their own apartments, and enjoy dating around. Her advice did include tips on how a woman could manipulate men's interests to her own benefit but it also had practical advice for self-sufficiency, advising them on budgeting, furnishing an apartment, and cooking. Nurse romance novels, too, often illustrate how women might exercise these options!

Male Characters in Romance Novels

Male characters in nurse romance novels believe all sorts of stereotypes about women—that they are innately inclined toward domsesticity, are hunting for a husband, have a lower intelligence, and are prone to hysterics and jealousy.

The protagonist always has two men (at minimum) competing for her affection. The men are opposites in many ways: finances, social status, and personality, as well as how they view marriage and women. One man will be dependable, rational, caring, and mild-mannered; the other will be adventurous, brilliant, passionate in his pursuits, and often emotionally indecipherable. The alpha-male characters are volatile, controlling, want a "traditional" wife, and make misogynistic remarks. They simultaneously challenge the protagonist’s independent sensibilities and hypnotize her. Her choice seems impossible (to her) as both men are handsome, smart, and successful, making it a hard choice. Once a reader understands the patterns of the nurse-romance novel, however, they will pick up on clues as to who is or isn't Mr. Right!

Though cover captions and cover art insinuate that the nurse will have to choose between nursing and marriage, rarely do the authors force their protagonist to choose. Rather, the trajectory of the entire narrative culminates in a moment when the protagonist comes to understand that her true love will not ask her to sacrifice her career. Either the protagonist will tame the demanding suitor to her will or cast him aside for one who understands her desire to work and retain some independence. Time and again, the protagonist will choose the man who supports her identity as a nurse.

Prompts for Critical Thinking

-

Romance fiction often presents contradictory messages about gender roles and dynamics. But many women who consider themselves feminists really enjoy romance novels. Are there ways to reconcile our personal reading habits with the critical reading practices we learn in academic courses?

-

Do you think that these nurse romance novels challenge historical interpretations that assert the mid 20th century was an era of conservative gender ideologies? Are they reflecting a reality that the era was more open than historians have assumed or are they presenting authors' and readers' fantasies of a more permissive society for women?