Rev. Gene Phillips Letters, 1970-2004

Item

- Title

- Rev. Gene Phillips Letters, 1970-2004

- Location

-

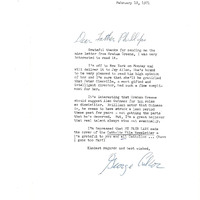

PAGE 1: Letter from George Cukor to Rev. Gene Phillips, Feb. 12, 1971.

Cukor thanks Phillips for sending a “nice letter” from Graham Greene, and states that he will pass it along to Jay Allen. Cukor comments on Greene’s choice of casting Alec Guiness[sic] (Guinness) and that he was impressed to see My Fair Lady on the cover of the Catholic Film Newsletter. Typed on Cukor’s own stationery, handwritten salutation and signature.

PAGE 2-3: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 17, 1971

Zinnemann states that he looks forward to meeting Phillips with the intent of possibly being included in a book of interviews. Zinnemann suggests July 25th and mentions to hearing about “Father Pat.” Typed on stationery with address 128 Mount Street, London, with handwritten signature in purple ink.

On the back: Appears to read “John [illegible] – program[?] for M of MA [Museum of Modern Art] 1967.” Below: “[MMA or AMA] – [illegible]: P1x9 & Zinnemann & All Quiet.” Handwritten in black ink.

PAGE 4-5: Envelope for letter to Rev. Gene Phillips from Fred Zinnemann

Air mail envelope, red and blue border. Addressed “The Rev. Gene Phillips, S.J., 6525 North Sheridan Road, Chicago, Illinois 60626-5385, U.S.A [double underlined].” Handwritten in green ink. Appears to postmarked 1986 or 1996, 41p Queen Elizabeth II grey-brown “Machin Definitive” stamp.

On the back: return address “98 Mount St., London W1Y 5HF, England.” Handwritten in green ink.

Note: was originally stored in same sleeve as Jun. 1971 letter.

PAGE 6-7: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 30, 1971.

Zinnemann continues a conversation he and Phillips had evidently had in-person about a script and/or a biographic work. Zinnemann provides comments and mentions the films The Nun’s Story (1950), From Here to Eternity (1953), High Noon (1952), Man for All Seasons (1966), and The Sundowners (1960). Typed on plain paper, numbered, with signature and minor corrections made in black ink. Lines “If I am not myself, who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?” underlined in red ink.

PAGE 8-9: Letter from Alec Guinness to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jan. 3, 1972.

Handwritten in blue ink on Guinness’ personal stationery. Guinness thanks Phillips for sending a copy of Phillips’ biographical writing about him. He also requests Phillips remove some details:

“I would be grateful if you would eliminate the knighthood story. The Sunday Times shouldn’t have published it and it is largely garbled anyway – by the necessity of brevity. It could put me in a slightly embarrassing position if it achieves traction publicly.”

Guinness also describes not taking a role in Cukor’s Travels with My Aunt (1972), along with Katherine Hepburn (who also ultimately didn’t take a role in the film,) alluding to Guinness potentially being too old for the intended role. He closes confirming that he may be playing Adolf Hitler in a film written by Wolfgang Reinhardt (Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973).) Date corrected in black ink, initially written as 1971.

PAGE 10: Envelope for letter to Rev. Gene Phillips, Dec. 7, 1981.

Sent via airmail. Postmarked 7:15PM on Dec. 7, 1981, from St. Alban’s, Herts. (Hertfordshire) in the United Kingdom. Return address P.O. Box 123, Borehamwood, Herts. U.K. Addressed as “Airmail” (underlined) to Rev. Gene D. Phillips, S. J., Loyola Uniersity, Faculty Residence, Chicago, Illinois, 60626, USA. Stamped with 22p Queen Elizabeth II blue “Machin Definitive” from 1980.

Note: was originally stored in same sleeve as Jan. 1972 letter. Further research suggests this may be Stanley Kubrick’s P.O. box.

PAGE 11: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 7, 1972.

Typed on “CHACAL” Universal Productions France stationery with signature and minor corrections made in blue ink. Zinnemann describes being “over [his] ears” shooting The Day of the Jackal (1973) and refers Phillips to PR representative Gordon Arnell for more information about production. Zinnemann is still unsure of the film’s quality, requesting Phillips say a “small prayer” for him.

PAGE 12-13: Letter to Stanley Kubrick from Rev. Gene Phillips and Kubrick’s response, Apr. 23 & 28, 1973.

Typed on aerogram with postscript, initials, and minor corrections made in blue ink.

On the front: Phillips informs Kubrick that he received a contract from Curtis Publishing Company to write a monograph of Kubrick’s work. Phillips requests Kubrick read his manuscript and recommends some of his previous works for reference, then mentions searching out 16mm prints of his films, namely The Killing (1956) and Paths of Glory (1957). Phillips includes a postscript listing other authors to be featured in the monographs series: Don Siegel, Preston Sturges, and Michael Curtiz.

Kubrick’s response, postmarked Apr. 28, 1973, handwritten below on blue ink: “Dear Gene – I am at your disposal to read the piece. If you have problems with getting any films, please let me know and I will help. Hope you are well. Best Regards. Stanley.”

On the back: hot air balloon aerogram with 3 hot air balloons printed, one with red, white, and blue with stars and two with blue outlines. Addressed to Mr. Stanley Kubrick, P.O. Box 123, Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, ENGLAND. Prepaid postage for USA, 15c. Below, upside-down, address stamped Gene D. Phillips, S.J., Loyola University, Faculty Residence, 6525 N. Sheridan Rd, Chicago, Illinois 60626.

PAGE 14: Letter from Stanley Kubrick to Rev. Gene Phillips, May 31, 1973.

Typed on Kubrick’s personal stationery, signature written with green ink. Kubrick expresses appreciation in Phillips’ interest in Barry Lyndon (1975) but requests that Phillips not ask him about the film before it’s finished. He also voices a predisposition against Phillips writing a “Day in the Life of” approach to writing about Kubrick.

PAGE 15: Letter to Stanley Kubrick from Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 7, 1973.

Phillips thanks Kubrick for a quick response and understands Kubrick’s reservations about the “A Day in the Life of” approach and asks for alternative suggestions. Phillips notes that there are items enclosed with the letter. Typed on plain paper, headed with “Faculty Residence.”

PAGE 16: Letter from Fritz Lang to Rev. Gene Phillips, Apr. 20, 1974.

Lang thanks Phillips for sending his book, Graham Greene: The Films of His Fiction. Lang comments on his failing eyesight before describing how flattered he was about Greene’s comments about Fury (1936) and agreed with his opinion of The Ministry of Fear (1944). Lang provides Phillips with his phone number and encourages him to visit in Los Angeles now that Lang, he says, is in better health. Typed on Lang’s personal stationery, handwritten signature in black ink.

PAGE 17: Letter from Fritz Lang to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 15, 1974.

Lang thanks Phillips for his visit and includes some corrections to Phillips’ manuscript of their interview. Lang requests Phillips visit again to record another time. Typed on Lang’s personal stationery, handwritten signature in blue ink.

PAGE 18-19: Letter from Peter Duffell to Rev. Gene Phillips, May 5, 1975.

Duffell apologizes for not replying to Phillips earlier, as he was shooting a movie (Inside Out, 1975) in February and recently returned. He thanks Phillips for his words about England Made Me (1973) and says he will write a thank-you note to Les Keyser. Duffell describes plot notes from Inside Out and comments on how critics will comment on his tendency toward featuring the Nazis in his films. Duffell then goes on to tell Phillips that a manuscript for a screen adaptation of Greene’s 1973 novel The Honorary Consul is in the works, finance is sorted, but Duffell has met a roadblock with distribution. Handwritten in blue ink on Duffell’s personal stationery.

PAGE 20-22: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 14, 1975.

Attached via staple. Zinnemann provides Phillips with a list of corrections to the latter’s writing about The Nun’s Story (1959) and some details from their interview, along with some requests for changes, including comments about The Seventh Cross (1944), Odd Man Out (dir. Carol Reed, 1947). And The Day of the Jackal (1973). Typed on 128 Mount Street address stationery, numbered, with handwritten signature in black ink.

PAGE 23: Letter from Saul Bellow to Rev. Gene Phillips, Sep. 18, 1975.

Bellow writes Phillips with commentary on a manuscript sent him. Bellow describes the writing as “quite interesting,” but “too scattered” with “themes lacking in detail.” Bellow finds that the manuscript is not currently publishable and that Bellow himself is “unable to offer to help,” though he had begun revising. Bellow describes a “stunning volume of noise” after the publication of Humboldt’s Gift (Bellow’s 1975 novel) and jokes that he plans to move to the Middle East to avoid the uproar. Typed on University of Chicago Committee on Social Thought stationery, handwritten signature in blue ink.

PAGE 24: Letter from Dakin Williams to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 9, 1976.

D. Williams explains that his friend, Ben Llamzon, had told him that Phillips was writing a book about Tennessee Williams. D. Williams reminds Phillips that he is running for governor, so he cannot write much. As Tennessee’s brother, however, D. Williams informs Phillips that he plans to write a biography about his relationship with Tennessee called My Brother’s Keeper (eventually titled His Brother’s Keeper: The Life and Murder of Tennessee Williams, published 1983). D. Williams includes some opinions he and Tennessee had about the adaptations of the latter’s plays, including The Glass Menagerie (1950; Tennessee allegedly tried to sue Warner Bros. over the happy ending), A Streetcar Named Desire (1951; Tennessee liked, though Dakin wished to have more original dialogue included), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958; “financial bonanza” Dakin still likes), Sweet Bird of Youth (1962; Dakin liked but wanted to see castration scene included), The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (1961; Dakin’s favorite but “virtually unknown to the public”), Summer and Smoke (1961; Dakin “loved” the play and found the movie “very fine”), and The Fugitive Kind (1960; Dakin believes it received a “bum rap” from critics and was underrated).

D. Williams goes on to describe his meeting Marlon Brando and Maria Bretneva – The Lady St. Juste, the latter who “married an insane British lord.” According to D. Williams, Bretneva tried to push Dakin down a staircase backstage at the opening of Out Cry in New York, establishing an antagonistic relationship. Brando, Dakin says, was silent that night because he was “projecting his Stanley Kowalsky[sic] role off-stage, as he had no real self-image of his own.” Finally, D. Williams tells Phillips, “Most actors, Including Newman, appear to be puppets to me.” Typed on stationery from Dakin Williams’ office as Attorney at Law, handwritten signature in blue ink at the very bottom of the margin.

PAGE 25: Letter from Peter Duffell to Rev. Gene Phillips Jun. 16, 1976.

Duffell thanks Phillips for sending a copy of the magazine that included the article on England Made Me (1973). Duffell expresses frustration with the film industry, as he is “still struggling” to adapt The Honorary Consul, though Duffell claims there is renewed interest from “the majors.” Duffell also describes a desire to work on an adaptation of the C.S. Forester novel, Death to the French (1932). Duffell also comments on a Variety review of “that piece of trash [he] made last year”—likely a reference to Inside Out—and expresses surprise at making its money back given that it “was no pleasure to make, the script was pretty dreadful and I had little or no rapport with the leading actors or for that matter the producer.” Typed on yellow stationery with address 111 Queen’s Road, Richmond, Surrey. Handwritten signature in black ink.

Note: Bottom of page cut off in scan.

PAGE 26: Letter from Peter Duffell to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jan. 24, 1977.

Duffell thanks Phillips for his note about England Made Me (1973) and comments that the review in question “wasn’t complimentary” because Phillips did not provide the publication’s name. Duffell goes on to mention that he went to the press show of Marathon Man (1976). He then updates Phillips on the lack of movement on the Honorary Consul adaptation project, but he received “a very healthy preproduction loan” from the NFFC, or National Film Finance Corporation and is going to Portugal to scout locations. He concludes by requesting Phillips visit if he is coming to England that year. Typed on yellow stationery with address 111 Queen’s Road, Richmond, Surrey. Handwritten signature in blue ink.

PAGE 27-28: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips and postscript, Jun. 13, 1978.

Zinnemann comments on Lou Giannetti’s analysis of The Member of the Wedding (1952), stating he did not agree with some of his opinions. He goes on to state that some of the comments he’d made in his interview with Phillips did not come across as intended, and so he rewrote the transcript. Furthermore, Zinnemann requests that Phillips not quote him unless he includes the postscript printed on the back of the letter. Typed on 128 Mount Street stationery. Handwritten signature in blue ink, along with underline on word “not” and “unless.”

Postscript: Zinnemann explains his function in the film was “rather limited” because he struggled to “get past the Mafia surrounding George Cukor.” He goes on to explain that the two are on friendly terms, but Zinnemann’s contract with Cukor was not renewed as Zinnemann was signed to MGM “shortly after Camille in 1937.” He goes on to state he is “superstitious” about sharing new projects and will “therefore keep things quiet.” Typed, handwritten signature in black ink.

PAGE 29: Letter from Mary Welsh Hemingway to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 20, 1978.

M. Hemingway describes her late husband Ernest’s thoughts on various adaptations of his work. According to Mary, Ernest only liked The Killers (1946), “made by a man, long dead, whose name [she] tried and tried to remember and cannot” (possibly Mark Hellinger, d. 1947, if not Robert Siodmak, d. 1973, as she says the name was Irish, but Edmond O’Brien was still alive at the time.) She recalls Ernest’s complaint about Gary Cooper’s “brand-new shirt from Abercrombie and Fitch” in a rugged scene in For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943). She speaks kindly of Fred Zinnemann, of whom Ernest was fond, and who was originally set to direct The Old Man and the Sea (1958), though she believed Zinnemann (misspelt “Zimmerman”) would not approve of the casting of his friend Spencer Tracey in the lead. M. Hemingway continues, stating that she had no clear memory of Ernest’s specific comments on other films, including the three versions of To Have and Have Not (1944, 1950,1958) and two versions of A Farewell to Arms (1932, 1957). She concludes with a memory of fishing for marlin during filming. Typed on stationery addressed P.O. Box 555, Ketchum, Idaho 83340, signature handwritten with blue ink.

PAGE 30: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Sept. 8, 1978.

Zinnemann thanks Phillips for the note about Hemingway. He recalls the first days of shooting, and that he did not quit because of Jack Warner “viewing the rushes.” He concludes with the request that “spurious gossip” be removed by “omitting the two sentences which contain my misspelt name” in reference to Mary Welsh Hemingway’s letter. Typed on 128 Mount Street address stationery, handwritten signature in black ink.

Note: Zinnemann types his signature with six N’s at the end instead of the usual two.

PAGE 31: Letter from Fred Zinnemann (unsigned) to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 16, 1980.

Zinnemann replies to a series of questions from Phillips. He says that Phillips was “partly right” about what George Cukor told him, stating that his first job in Hollywood, in November 1929, was an extra on All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) before being fired by an Assistant Director. Cukor, he says, had also just arrived in Hollywood from New York. After Zinnemann worked with Busby Berkeley and Gregg Toland, Cukor later hired him in 1936 for Camille (1936) with Greta Garbo and Robert Taylor. Typed on 128 Mount Street address stationery, unsigned.

PAGE 32-33: Postcard from Irving Thalberg, Jr. to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jul. 28, 1980.

On the front: Addressed to “Professor Gene D. Phillips, S.J.” at Loyola University, Faculty Residence, 65626 N. Sheridan Road, Chicago, Ill. 60626, typed. Return address on an address sticker, marked as Irving Thalberg, Jr., with two addresses. On the right: dated March 25-Dec. 5, Dept. of Philosophy, Univ. of Ill. At Chicago Circle, Box 4348, Chicago, Ill. 60680, Phone (312) 996-5677 or 996-3022. On the left, dated Dec. 6-Mar. 24, Box 2437, Aspen, Colo. 81611, Phone (303) 925-7316, with “SUMMER &” handwritten in pen over “Dec. 6-Mar. 24.” Postmarked July 30, 1980 from Glenwood Springs, CO. Stamped with an orange “Hancock Patriot” U.S. Postage stamp with image of John Hancock, 10c. Postcard copyrighted 1978.

On the back: Thalberg offers to provide information he can for Phillips’ book on George Cukor, though he says he cannot say much on Hollywood during the “years when [he] was old enough to understand the milieu—say from 1942-1948” (a “4” is typed over a “5” to correct writing “1958”.) Thalberg states that his mother (Norma Shearer) retired from social life after his father died in 1937, and from film in 1942. He goes on to say that he has not resided in Los Angeles since going to a Swiss boarding school in 1948, then Stanford the following year. He recalls Shearer’s “admiration” for Cukor and her “feeling that he got top performances from her and many other actors and actresses.” Typed, with “-ny other actors and actresses” and his signature handwritten with black ink.

PAGE 34-35: Letter from George Cukor to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 13, 1980.

Two pages, attached via one staple. Cukor’s introduction brags that he instructed CBS to run The Corn is Green (1979) so that his “pal” Phillips could see it and assume Phillips that Cukor is a “Big Shot.” Cukor goes on to write about why the “proud name” of James Constigan does not appear in the film’s credits. Cukor informs Phillips that the actor and screenwriter uses “James Constigan” as a stage name; then, he refers to Constigan as “difficult” and that he “could say ruder things about but him but [Cukor] must remember that [he is] writing to a man of the cloth.” Constigan allegedly did not provide a script for Cukor and actress Katharine Hepburn: Cukor claims that when Constigan realized Cukor and Hepburn weren’t using his script but another’s, Constigan “behaved stupidly,” “pretentiously,” and had his name removed from the credits. Cukor then asserts that Hepburn actually wrote this script for The Corn is Green, referred to her as hardworking and clever, and asks Phillips to not mention this incident.

Cukor moves on to report that Love Among the Ruins (1975) was nominated, but did not win, the (unnamed) award for “the best production.” Cukor says that he does not remember whether Don Stewart did any writing for The Women (1939) due to there being multiple writers who would “help out” during “the good old days.” He compliments Irving Thalberg, Jr. and his father, and tells Phillips that he will be in London in September to appear for The Guardian at a screening of a series of MGM films, including Camille (1936) with Greta Garbo.

Cukor includes a postscript, mentioning that he included a transcript of an interview he’d given for the Hollywood Bowl that he does not remember giving, mentioning the names of two people involved he did not like—Beverly Gray and Vanessa Redgrave—and one he did like—Jim Hansen. Typed on George Cukor’s personal stationery. Salutation and signature handwritten in blue ink, two exclamation points added after the opening sentence in blue ink, and a typed underline in black to emphasize “am” in the second sentence of the letter’s opening.

PAGE 36: Letter (photocopy) from George Cukor to Dr. John Shea, Oct. 2, 1980.

Cukor writes to Shea as a recommendation letter for Rev. Gene Phillips to become a professor at Loyola University of Chicago. Cukor compliments Phillips’ abilities as a film historian to Shea, chair of Department of English, and goes on to stress the importance of film in the college curriculum. Typed on Cukor’s personal stationery, handwritten signature, with “Doctor of Humane Letters, Loyola University of Chicago” typed beneath it.

PAGE 37: Letter from Henry King to Rev. Gene Phillips, Sept. 30, 1981.

King compliments Phillips on his book, telling Phillips that Gregory Peck was “delighted” with Phillips’ writing on The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1952). He also states that he received his copy of American Classic Screen and that while his ill health and poor eyesight keep him from reading, he hopes this will change soon. Typed on Henry King’s personal stationery, handwritten signature in black ink, with a "w" added into the title of The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

PAGE 38: Letter from Stanley Kubrick to Rev. Gene Phillips, Dec. 5, 1981.

Kubrick asks for Phillips’ forgiveness in responding so late to Phillips’ July 1980 letter, as it had been sent to Kubrick’s previous residence and was then misplaced in the mail before being found again. He says that he is glad Phillips liked The Shining and remarked on the love/hate response from critics, though it was well liked by audiences because it was his most commercially successful film to date. He asks if The Times printed Phillips’ letter and hopes they meet again soon. Typed on plain paper, handwritten signature in black ink with multiple corrections. Kubrick includes a handwritten postscript at the bottom of the page, clarifying that he moved to St. Albans, some distance from London.

PAGE 39: Letter from Irving Thalberg, Jr. to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 24, 1983.

Thalberg thanks Phillips for conducting a memorial service for his mother, Norma Shearer (died Jun. 12, 1983). He also lets Phillips know that several of Shearer’s granddaughters (including two of his own daughters) are aspiring actresses. Handwritten in blue ink on stationery from University of Illinois at Chicago Circle.

PAGE 40: Letter from Frances Scott “Scottie” Fitzgerald (incomplete) to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 9, 1983.

Fitzgerald Smith provides her thoughts on the quality and faithfulness of various adaptations of her father, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s, writing. She includes mention of The Great Gatsby (1974), Bernice Bobs Her Hair (1976), Winter Dreams (1957), The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954), Tender is the Night (1962), The Last of the Bells[sic] (The Last of the Belles, 1974), and The Last Tycoon (1976). She criticizes the casting choices of The Great Gatsby in particular; while the Fitzgerald estate was given the right to approve the script, she felt that Mia Farrow’s strengths as an actress do not apply to the “intensely Southern and feminine” Daisy and that casting “the most famous movie star in America” (Robert Redford) as “one of American fiction’s most elusive characters” (Jay Gatsby) was a poor choice. She goes on to describe how many scholars describe her father’s writing as “impossible to translate.” The page cuts off with “I do not,” suggesting she disagrees, but the second page of this letter is not included in this archive of letters. Typed on plain paper.

PAGE 41-42: Letter from Frances Scott “Scottie” Fitzgerald Smith to Rev. Gene Phillips, Sept. 13, 1983.

Fitzgerald Smith opens by joking that she had not seen the Woody Allen film Phillips mentioned in his previous letter (likely Zelig [1983]) as “Woody is too sophisticated for the folks down here… & this new one may never come [to theaters]!” She continues by answering the question of why she liked The Last of the Belles (1974), which was primarily due to casting of Richard Chamberlain and Blythe Danner. Fitzgerald Smith also praises the “evocative” settings but hopes that “a movie is never made of [her parents’] lives” because of the “clichés and exaggerations.” She concludes stating that The Last Tycoon (1976) was the worst adaptation, as it was the hardest to make and the hardest book to understand (and that she doesn’t understand it.) Typed on Fitzgerald Smith’s personal stationery, handwritten signature in blue ink with a handwritten exclamation point after her point that she didn’t understand The Last Tycoon.

PAGE 43: Letter from Frances Scott “Scottie” Fitzgerald Smith to Rev. Gene Phillips, Sept. 21, 1984.

Fitzgerald Smith gives Phillips permission to write about any and all of Fitzgerald’s adaptations. She also mentions that the BBC is planning to adapt Tender is the Night to a television series (released 1985), which she hopes will “dispel the myth that [her] father’s stories are not translatable” as they did with Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1981). Handwritten in green ink on Fitzgerald Smith’s personal stationery.

PAGE 44-45: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, Feb. 15, 1985.

Forbes provides an update of what he has been up to since he last spoke with Phillips. For written works, he includes novels The Distant Laughter (1972), Familiar Strangers (1979), and The Rewrite Man (1983) and nonfiction books Notes for a Life (1974), Ned’s Girl: The Authorised Biography of Dame Edith Evans (1977), That Despicable Race: A History of the British Acting Tradition (1980). As for films, he mentions International Velvet (1978), Sunday Lovers (1980), Jessie (1980), The Naked Face (1984), and Better Late Than Never (1983) which was originally titled Menage a Trois but changed after the death of David Niven due to it being his last major role. Forbes includes some insights on various productions among this list and offers to send photographic material to Phillips for any projects, should they come to Forbes. He also finally says that his effort to secure the rights for The Honorary Consul was unsuccessful but appreciated hearing Graham Greene’s comments on the topic. Typed on Seven Pines stationery with Bryan Forbes Ltd.’s logo, signature handwritten in blue ink.

PAGE 46: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 17, 1987.

Zinnemann greets Gene and requests he let Zinnemann know when the updated Movie Makers will be published. He goes on to list “a number of very talented men deserving of your attention” that were not included among British Directors. He names Michael Radford (specifying Another Time, Another Place [1983] and 1984 [1984]), Mike Newell (Dance With a Stranger [1985]), Neil Jordan (Mona Lisa [1986]), Jack Gold, Lindsay Anderson, Alan Bridges, Bruce Beresford, and Jack Clayton. Zinnemann identifies Gold and Redford as the strongest talents in his opinion and suggests the inclusion of Alan Parker. Typed on 128 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature and inclusion of Bruce Beresford and Jack Clayton in blue ink.

PAGE 47: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, May 23, 1988.

Zinnemann thanks Phillips for the program note and recording of music for The Wave (Redes, 1936). Zinnemann says he was not “particularly upset” by the description identifying The Wave as “Paul Strand’s film,” though he clarifies that he found Strand to be a “great photographer… also a great egomaniac.” He also asks for Phillips’ thoughts on the ending of Five Days One Summer (1982), which he states was based on the short story “Maiden Maiden” by Kay Boyle. Typed on 128 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature in black ink.

PAGE 48: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 30, 1988.

Zinnemann begins stating that he would be “delighted” to be a dedicatee in Phillips’ latest book and sharing the honor with George Cukor. He also refers to two articles from American Film magazine both titled “Dialogue on Film:” one by Carl Foreman (Apr. 1979) and the other by Stanley Kramer (Apr. or May 1973). He then says Phillips is perhaps aware of “the entire affair” about High Noon (1952) that it is “probably too late to do much about it anyway” and Zinnemann “just thought [he] would mention it.” He concludes saying he was “fascinated” by the clip from the New York Times Book Review, says he is sorry to hear about Mankiewicz, and “did not expect anything different from Sam Spiegel.” Typed on 128 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature and note of reference to High Noon on blue ink.

PAGE 49: Letter to Stanley Kubrick from Rev. Gene Phillips and Kubrick’s response, Jul. 11, 1988 & Jul. 19, 1988.

Phillips informs Kubrick of a revised edition of The Movie Makers (Major Directors of the American and British Cinema) is going into production. He asks if he may quote Kubrick based on a letter in their correspondence about The Shining (1980). Phillips also states he will pull from Stanley Kubrick: A Film Odyssey (1977) for Barry Lyndon (1975) and an interview between Kubrick and Gene Siskel for Full Metal Jacket (1987). Typed on Loyola University of Chicago stationery, handwritten signature in blue ink.

Kubrick’s response included at the bottom of the page, along with annotations to Phillips’ message. Kubrick says he looks forward to the new edition, but also asks that Phillips not use the quote from their correspondence, as he does not like it. Handwritten in blue ink.

PAGE 50: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jul. 18, 1988.

Forbes approves of a quote Phillips asked permission to use in his letter. He states he is short on time to write, as he is shooting The Endless Game (1989) based on Forbes’ own novel of the same name (1986). Typed on Seven Pines stationery with Bryan Forbes Ltd.’s logo, signature handwritten in blue ink.

PAGE 51: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, Dec. 6, 1988.

Forbes provides details regarding The Endless Game (1989), which Forbes was in the process of editing at the time. He states that it is based on his 1986 novel of the same name, its cast (Albert Finney, George Segal, Derek de Lint, Nanette Newman, John Standing, Ian Holm, Anthony Quayle, and Kristin Scott Thomas), its being shot in Austria and England for a four-part miniseries, and that the novel was published in seventeen languages, spent sixteen weeks on the English bestseller list, and that he is working on a sequel. Typed on Seven Pines stationery with Bryan Forbes Ltd.’s logo, signature handwritten in black ink.

PAGE 52: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jun. 20, 1994.

Zinnemann notes that he is glad to hear from Phillips “after all these years” and learn that Phillips is working on a new book. Zinnemann then describes how directors are trying to establish “Moral Rights of authorship” for their work in film, to “protect it from mutilation.” He goes on to describe struggles with opposition from the industry and “apathy” from the public due to the lack of media coverage of the issue. Zinnemann asks Phillips to help them further public awareness of this issue, as there is a threat of “destruction” to their “cultural heritage” of cinema in Europe and the United States. Typed on 98 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature in black ink and “Can you help?” underlined.

PAGE 53: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 3, 1995.

Zinnemann addresses Phillips’ intent to include him in his new book project, approving. He then addresses how he and another man (William Wyler?) have different memories of the same incident. Zinnemann says he will not argue about Dodsworth (1936), but that there may be a mistake, naming These Three (1936). Zinnemann ultimately states that his point is that Wyler spoke to him, “in a human way,” and that Zinnemann found it “astonishing and memorable” that Wyler would be so civil in his reaction to a “wildly improbable situation,” and refers to their use of the “same dialogue.” Typed on 98 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature in blue ink with “me” underlined to emphasize that it was Wyler who spoke to HIM.

PAGE 54: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Aug. 18, 1995.

Zinnemann comments on an imaginary review of Man’s Fate (1969, abandoned film adaptation of André Malraux’s novel of the same name with Zinnemann set to direct). Regarding The Member of the. Wedding (misprinted as A Member of the Wedding) (1952), he states that he was unaware of 20 minutes being cut from the film but admits he may not remember well if anything of importance was omitted. He also mentions Brandon de Wilde, how he died young. He also corrects a point made by a biographer of Montgomery Clift, stating that Zinnemann’s first film was Redes (1936) and Clift’s was Red River (1948), released after The Search (1948). He also remarks on Hitchcock’s “The Crystal Trench” (Alfred Hitchcock Presents, season 5, episode 2, 1959) and compares jokingly to Five Days One Summer (1982). Typed on 98 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature in black ink.

PAGE 55: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Oct. 24, 1995.

Zinnemann thanks Phillips for sending him the new book, adding that he nearly adapted two films of Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness, but “those other boys beat me to it.” Comments on difficulty writing by hand, as it is getting “a bit shaky.” Typed on 98 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature in black ink with exclamation point after “Happy Thanksgiving.”

PAGE 56: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jan. 22, 1996.

Full letter transcription:

“Dear Gene,

Many thanks for your letter. In reply to your question and to the best of my memory: I attained American citizenship in March, 1937 at the Federal District Court in Los Angeles.

I look forward with anticipation to the time when your book has been published.

Kind regards,

FRED ZINNEMANN.”

Typed on 98 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature in black ink, though appears to be faxed with low ink so letters are faded.

PAGE 57: Letter from Fred Zinnemann to Rev. Gene Phillips, Feb. 9, 1996.

Zinnemann thanks Phillips for sending him a photocopy regarding A Man for All Seasons (1966), stating that he is “of course unable to arrive at an opinion of [his] own.” Zinnemann then mentions that a “youngish” film historian, Adrian Turner, visited him about a biography about Robert Bolt, and asked about A Man for All Seasons. Zinnemann apologizes for not getting approval from Phillips about a chapter but sent it to Turner since it was already published. Typed on 98 Mount Street stationery, handwritten signature in black ink.

PAGE 58: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jan. 12, 1998.

Forbes relays to Phillips an experience of a film being cancelled while in Montreal, describing how Forbes had written the screenplay and was finding a crew and choosing locations, then left with a hotel bill and had to finance his own return home. He says the film will likely never be released, so he believes there is little to include in any updated writings about that topic. Forbes goes on to state that he completed a trilogy of novels: The Endless Game, A Spy at Twilight, and Quicksand. He also mentions an addition to an autobiography and another novel titled Partly Cloudy. Typed on Seven Pines stationery with Bryan Forbes Ltd.’s logo, signature handwritten in black ink.

PAGE 59: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, May 25, 1998.

Forbes writes from Arizona, where he is writing a novel. He mentions “The King in Yellow,” an episode of a British/American co-production (Philip Marlowe, Private Eye). He was set to direct two of these episodes but was prevented by a producer who wished to direct, then ran out of funding for Forbes’ second episode. Forbes states that he did not know Ray[mond Chandler] well, but met him and knew his publisher, Roger Machell with Hamish Hamilton Ltd., who was also Forbes’ best man at his wedding. According to Forbes, Machell was the person Chandler called when he attempted suicide, with Machell alerting the police. Forbes relays to Phillips that Hamish Hamilton struggled to find lodging for Chandler because of his alcoholism and resulting issues. Forbes also describes meeting a variety of American authors through Machell, including Alan “Jock” Dont, Rene McColl, Paul Dehn, Truman Capote, and Sam Behman. Typed on plain paper, handwritten signature, corrected location of Chandler’s attempted suicide from Loyola to San Diego, faxed with low ink so letters are faded.

PAGE 60: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, Jul. 13, 1998.

Full letter transcription:

“Dear Gene,

In reply to your latest missile!

1. I have no idea why Powers Booth did not narrate the series.

2. Because Chandler was such an individual writer and chose to set his Marlowe stories in a particular period, updating them always seemed to me to water them down for no particular good reason. The actual locations which we used and which, at the time, still existed in reasonable condition (i.e. they had not been bulldozed and replaced by high rise apartments) gave the films an authenticity.

3. You are very kind to offer to dedicate the book to me and I accept graciously as they say – thank you so much – very flattered.

4. I will continue to search for cuttings and it would help if you could tell me the year I shot my sequence and then I can narrow it down to one of my 30 or so Press Cutting books! If I find them I will certainly cull anything of interest and send them to you.

Fondest regards,

Bryan Forbes”

Typed on plain paper, handwritten signature, faxed with low ink so letters are faded.

PAGE 61: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, Dec. 17, 2004.

Forbes writes Phillips to clarify some questions. Forbes claims he was an arbitrator for the Writers Guild’s efforts to establish the authorship of The Bridge on the River Kwai (misprinted Bridge on the River Quay) (1957), rather than for Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Carl Foreman, Forbes alleges, claimed it was his script, and David Lean in response said to Forbes: “If he persists any more I’ll show people the script he wrote.” Forbes says he helped to establish Michael Wilson deserved credit. Forbes states he was not aware of contention regarding Lawrence of Arabia. Forbes also responds to a comment made by Christiane Kubrick, which he claims is untrue, stating that while he lost contact with Stanley Kubrick in the years Kubrick “became a recluse,” he knew him well, along with Peter Sellers and Calder Willingham. Forbes asserts that he wrote to Kubrick on Malcolm McDowell’s behalf, that Kubrick nearly blinded McDowell during filming, and that Kubrick had sent Forbes an angry letter telling him not to “interfere.” Typed, faxed, with heading for “Nanette Newman & Bryan Forbes CBE”, handwritten signature.

Note: Forbes adds in the margin, in response to not knowing about the Lawrence of Arabia contention, a joke that he may be “senile.” He also states that he “certainly did not advertise” his opinion he’d typed that Kubrick’s final film was “piss poor and unintelligible.”

PAGE 62: Letter from Bryan Forbes to Rev. Gene Phillips, Dec. 22, 2004.

Forbes continues his comments on industry gossip/discourse. He concedes that he has likely forgotten that he helped to arbitrate on Lawrence of Arabia. He also disputes the claim that he had insulted Kubrick in front of his wife at a dinner, claiming they’d never dined together. Forbes also recounts an alleged interaction between him and Carl Foreman, claiming that Foreman convinced Forbes to write a script, under Foreman’s name, for The League of Gentlemen as a vehicle for Cary Grant. Forbes then learned that Foreman sold the script to Basil Dearden for 18k pounds, and when Forbes informed Dearden he’d written the script, they confronted Foreman, who backed down. The result, Forbes says, was the founding of Allied Film Makers. Forbes confirms his knighthood was bestowed that autumn, and wishes Phillips a Merry Christmas. Typed, faxed, with heading for “Nanette Newman & Bryan Forbes CBE.” - Date Created

- 1970-2004

- Site pages

- Letters

- Fred Zinnemann

- Works by William Faulkner

- High Noon (1952)

- The Member of the Wedding (1952)

- The Search (1948)

- Redes (The Wave) (1936)

- The Seventh Cross (1944)

- From Here to Eternity (1953)

- The Nun's Story (1959)

- The Sundowners (1960)

- A Man for All Seasons (1966)

- The Day of the Jackal (1973)

- Five Days One Summer (1982)